An Interview with Ernest A. Burguières, III for the Ernest A. Burguières Branch

This interview between Ernest A. Burguières, III and OJ Reiss took place in March 2014 at the office of Ernest Burguières in downtown New Orleans. Gertrude Pfost was also present and contributed to the conversation. Ernest has the distinction of serving two times on the Board of Directors of The J.M. Burguières Co., Ltd. and has been involved with Company matters for many years.

OJ - Ernest, I didn't know your parents well, particularly your mother, Virginea. Tell me about her.

EB - She was originally from Laurel, Mississippi. Sometime in the 1940's, her family moved to Bush, Louisiana. She was one of nine siblings, and most of those were girls. She was in the middle of the group, and sometime during that period she won a scholarship to LSU, and because of family considerations could not go. There were financial issues. Her father was a strong person and she inherited that characteristic from him. Later, she had a column in the States-Item which was an afternoon newspaper in New Orleans. She wrote about and covered the Caribbean circuit during the 1950's. She interviewed political figures like Juan Peron and wrote about Cuba before the revolution.

Later my mother went to work for Victor H. Schiro, who was mayor of New Orleans from 1961-1970, and was with him for about eight years. Then she went to work for F. Edward Herbert, running his office right across the street from where we are right now. My parents married in 1948 and they lived in the French Quarter. My dad was very gregarious and pursued my mother. He loved Jeeps and they were members of a group in the Quarter called the Royal Street Rounders.

OJ - Let's talk about your childhood.

EB - In retrospect, it was a very exciting time. In the 1950's, my father had an air-conditioning company. After WWII, air-conditioning was something new. With a sense of adventure, my father decided to move to Nicaragua in the mid-l950's for a couple of years. I was very young. It was very exciting for a five-year-old. Then we came back to the States and later moved to Mexico City for another couple of years. Dad worked for Raymond International, which was a construction company, and ran their Mexico City office. My father loved the Latin culture and had gone to Santa Clara University in California. He was a civil engineer by training but by avocation, he was a poet, an artist, and an inventor. He painted, sculpted, wrote poetry, and created pottery. I have some pieces of his art, but not many.

OJ - What about your high school years?

EB - We came back to the States from Mexico in the 1960's. We lived on Audubon St. in New Orleans and I went to Audubon School on Broadway. From there we moved to Constantinople St. in uptown New Orleans. I went to Wright School on Napoleon Ave. and Wright McMain on Nashville Ave. I remember that time because my father got a beautiful big Jaguar Mark 10 and a couple of other cars. He built a chicken coop in the back of our home and had chickens, ducks, and other kinds of animals. He also put what looked like a big cistern in the back yard that became our club house. When I went to Camp Greenbrier in West Virginia, it took him what seemed like a week to get up there because the Jag kept breaking down.

Gertrude - Tell us about your sister Holly.

EB - She's two years younger than me, born in November 1953. She went to Holy Name for grammar school then to Sacred Heart Academy for high school. Then she went to Spain to study art for a couple of years and she also went to school in Mexico. She stayed there, got married and had her son, Gordon. She's a New Yorker now and lives in Manhattan.

OJ - What kind of relationship did you have with your dad?

EB - It was a good relationship. He was a nostalgic person and didn't like conflict, conflict of any kind. He could not understand how people could keep grudges and be evil about things. He told me one time when he went to Philip Burguières father's funeral, he was shocked that he was the only member of our part of the family who went. Dad didn't think that was right. To Dad, family was family, and you put differences away when someone died. That's how he felt. There were tremendous differences in our family, but my father always tried to maintain relationships. There were bad things that people did to him that I didn't understand. I couldn't understand why he would ever talk to those people again. But he did, and just moved on. During the war, he was at Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and was at church when the bombs started falling. He didn't tell me much about that except that women took their petty coats and tore them into bandages. The ship he was on, the USS Cassin, was sunk. After that, he came back to the States and took training and was given command of a destroyer escort ship, USS PC-1138. He spent four years in the Pacific and the only stories he told me were about the time he spent fishing off the back of the boat.

The other story was about his getting involved with a sailor who bullied everybody and beat up a smaller guy. My father finally put the bully in a Marine prison, but was very upset because he knew how harsh the Marines were to inmates in their prisons. He cried about what would happen to the guy. That's all he told me; he never mentioned anything about combat. I have since found out that his ship was involved in the mop-up activities in the Solomon Islands. Submarine chasing operations were involved, but I never heard anything about that from him. After he died in 1983, my mother found a box of poetry that he wrote during the war.

OJ - He came home unscathed?

EB - Physically, yes; emotionally, no. He was definitely affected. Later, he was involved in an automobile accident where his head was injured. He ended up having a steel plate put in his head. Putting aside the automobile accident, I'm sure the war affected him because he never liked conflict and could not understand how people could hurt each other.

OJ - What about your grandfather, Ernest A. Burguières, Sr.?

EB - I don't remember much about him. He was a very sweet person with some unusual habits. In the 1920's, they lost two children to whooping cough, Isabella (1921-1923) and Leila (1924-1925). In those days no one knew how the disease was contracted. At birthday parties he never let anyone blow out the candles because he thought that germs could spread.

Gertrude - Do you remember going out to the country as a child?

EB - I sure do. I got my first BB gun from Ed Burguières. I found a picture that I posted on Facebook of the famous alligator that lived in the swamp right below the house that Ed lived in. He'd make a funny sound and that alligator would come up out of the water, open his big mouth and Ed would throw a chicken to him. Ed was an interesting fellow. He always reminded me of that great cartoon character, Fog Horn, Leg Horn. He really was interesting. In reading the various things that happened, I think that Ed was a provocateur, playing both sides of an issue.

OJ - How did you meet your wife, Dorothy Winn Venable?

EB - I was trying to meet girls and it wasn't productive to go to bars, so I went to charity fundraisers. She was working at one and we started talking. Things led to things and we were married on December 2, 2006. We currently live in old Mandeville, about a block and a half off the lake. We've been there about 10 years.

OJ - What was it like growing up in New Orleans?

EB - Growing up in uptown New Orleans, we all had the same group of friends. We went to different high schools, but most of us belonged to Valencia, which was an uptown teenage club. We weren't wealthy, but we were comfortable. We had a more emotional attachment to my grandmother's side of the family, the Moore's, than we had to the Burguières side. My father had good memories of the Moore's. I've always wanted to know more about the Burguières, but my father's interest was always on the Moore side. As a child, Dad spent a lot of time with Robert Moore, his grandfather, and not much with his father, Ernest Burguières, who was always working on the plantation. Robert Moore died in the 1940's. He had become a merchant banker with houses in New London, Conn. and, for a while, owned 2525 St. Charles Ave. here in New Orleans and also the St. Charles Hotel downtown. He was pretty wealthy but, by the time he died, there just wasn't much left. He started from very humble beginnings in Liverpool, England and became very successful. He kept a diary which was like a book. I may get it published someday. It was the story of his journey through America. He tells interesting stories.

My curiosity about the Burguières name and history has always haunted me and I've since connected with a Burguières family from France. Gertrude, I knew you and your brother Sam, and of course I knew your mother and father, but that was about it. I'd go see Aunt Louise when she had an apartment on St. Charles Ave. I remember visiting Henry, your uncle. And, of course, when we went to the country, we always visited Ed, who was a lot of fun. I knew Duts, Al Burguières, who played quarterback for Tulane. I didn't know any other members of the family until the early 1980's when I discovered this huge part of the family that I didn't know about.

Gertrude - When were you put on the Board of Directors to represent the Ernest family?

EB - In 1978, I was put on the Board. We met twelve times a year and we got $100 each month. I was in law school then. We would go over the business of the Company; typically, we would meet in the Milling Law firm conference room in downtown New Orleans. Sam and Ed Burguiéres were there, and I can't remember who else met with us. We would review the bills that the Company had received. Henry Pierson was a partner of the Milling firm. Just as an example, there would be a February legal invoice for, let's say, $2,300 for services rendered; then another one for March maybe in the amount of $3,700 for services rendered. That was it! No detail; no nothing. So I asked Mr. Pierson if we had been involved in any litigation and he responded, no. Then I asked him what he had done to earn that amount of money? Gertrude, your father got very upset. He chastised me for questioning the integrity of Mr. Pierson. It wasn't long after that, in 1980, when I was pushed off the Board.

OJ - Do you really think that was the reason you were removed from the Board?

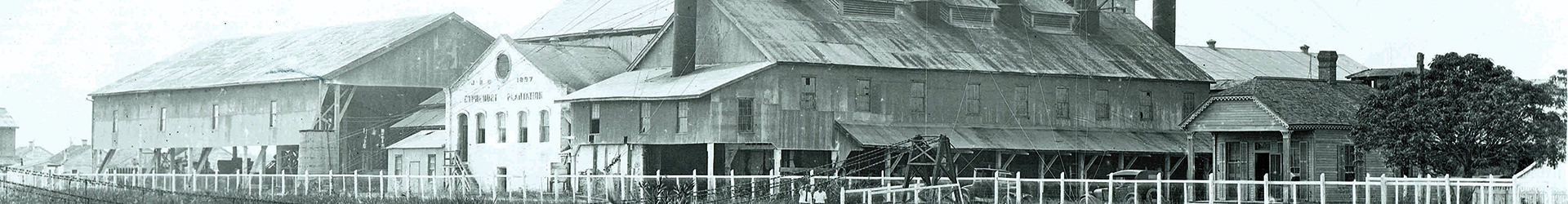

EB - Abner Hughes and Henry Pierson were there and they pretty much ran the Company. Abner had about 20 percent of the stock because he represented the Jules Trust and that was a source of a lot of friction. There was not a lot of activity going on then. Ed was on his way out and we had sold the sugar mill sometime in the mid to late 1970's. The sugarcane land had been leased out to farmers for operation. We had a little bit of oil and gas activity and we had the salt mine. That's was about it. So there was very little money and very little activity.

OJ - Who was on the Board with you in 1978?

EB - Sam Burguières, Sr., Ed Burguières, Marion Clerc, Abner Hughes, Ron Cambre, Philip Burguières and myself. There were things that happened that I just did not understand. For example, there were all these houses on the property that I thought should be restored and cared for. Why not lease them out? But everyone was against that because managing the leases would be too expensive. So the houses were left alone and all fell to disrepair. A form lease could have been used and approved by a lawyer and the proper insurance purchased. That's all it would take, and we could have taken care of a standing asset. Nobody wanted to fool with it, and I was amazed by that.

OJ - Fill in that time for me after you graduated from high school.

EB - I graduated from de la Salle high school in 1969 and then went to USL and studied architecture for two years. I came back to New Orleans and became an English major, then became a political science major, then a business major, and then in 1975 I went and worked with a survey crew in the oil field. I did some work on foreign cars, then went to UNO at night, then transferred to Loyola and got a Bachelor of Business degree in the mid-1970's. In 1977, I started law school at Loyola and, in 1978, found out that I could go to school without paying tuition because I was paying my own way. I started graduate school at night and went to law school during the day. I graduated in 1980 and was one of the few people who graduated with a business degree and a law degree. I took and passed the BAR in 1980.

OJ - What did you do then?

EB - I practiced law by myself for a while and was on the JMB Board while I was in law school, as I mentioned. Anyhow, I did various things and rented an office in this building in 1999. In the mid-1990's, I was appointed Commissioner of Conservation under the Gov. Edwards' administration for about two years. I learned an awful lot about the oil and gas business, learned a lot about Louisiana, and a lot about government bureaucracy. One of the things I could never understand is why JMB didn't buy oil leases around its property. If we had bought leases, we would still have been in a passive operation mode and that's in line with how the Company has conducted itself through the years. A lot of mature wells are still producing a lot of hydrocarbons. I learned a significant term in oil and gas production; it's "Lifting Costs." What it means is that when Texaco drills a well they may have a $15 per barrel Lifting Cost. Texaco is a very big company with tremendous overhead. That $15 is what it costs them to get a barrel of oil out of the ground. A smaller independent company like Stone Energy might have a Lifting Cost of only five dollars per barrel for the same barrel of oil. That's a ten-dollar difference. And a lot of guys got very wealthy on that disparity. Pat Taylor of Taylor Energy was with Shell Oil. He was a geologist working in a large field before he retired. Shell wasn't doing anything with the acreage, so Pat acquired the lease. He knew there was oil there, but it was too expensive for Shell to get it out of the ground. But he knew he could, and he did. He made millions of dollars. If you've ever seen a big company operate, you'll see they have enormous overhead. A small company like Taylor Energy can pivot on a dime. That's the difference. I knew a guy in Baton Rouge who was a geophysicist and geologist. He was a billionaire. These guys can smell oil. He would smell opportunities that no one else saw. If I was JMB, I would partner up with a guy like that and let him drill on one of our leases. I think that would be an interesting play. I know guys who are buying up old gas pipelines for the right time in the future.

Gertrude - Do you think the Company should bring outside management in for Board-level, paid positions?

EB - I think you can put together a board of bright, educated people who are family members; people who care and can communicate with Glenn Vice about opportunities as those opportunities present themselves. I think it's a mistake to remove family members from an overview of operations on a day-to-day basis. To not know what's going on and to assume that honesty exists is wrong. Certainly, the family Board members have to stay abreast of things as those things present themselves. I don't think we currently have that right now. I don't think everybody has the interest. That's where we have a disconnect. Not everybody on the Board has the ability or interest to look at things the way they ought to be looked at.

OJ - I'm interested in your feelings about the purchase of the land in Texas. Was it a good investment? Does the water issue make sense?

EB - These are just personal opinions, but I don't think we should have bought the ranches. I think we should have bought land around St. Mary's Parish. If your goal is to make money, there's tremendous opportunity in south Louisiana. And, it is easier to manage. The Texas thing was just personal, I think.

OJ - You mean a guy who owns a piece of an NFL team buys a ranch?

EB - Yes, it's a place to hunt quail and deer. There are people in Houston and Dallas that own big spreads in West Texas - 5,000, 10,000, 50,000 acres. I've hunted on those properties. West Texas has beautiful lunar beauty about it, but I think we could have spent the money in a wiser way. I think it was a missed opportunity. It's turned out to cost less than I thought it would, but I don't think it was the best investment we could have made.

OJ - Let's move forward to the second time you were asked to join the JMB Board in 1997.

EB - At that time Ron and Philip were working very hard trying to re-structure the Company. At one time they were attempting to change the Company into an S Corp., another time into a Partnership. There was a lot of mistrust at that time about their motivation. I didn't really know Ron or Philip then. My mother was very suspicious of them and we just chose to not participate.

OJ - Why was your mother suspicious?

EB - It wasn't just my mother. People were suspicious for reasons I don't remember. In the early 1960's, my father had filed suit against the Company and had it thrown into receivership. I think that was for lack of representation on the Board. There were five families involved and there should have been Board representation for all of the families. Usually, every family would have one representative on the Board. Without the full representation, communication ceased. There was also a lot of intrigue from the Patout family. Patout was very strong-willed. He wrote a letter at age 16 stating that he was very upset that he could not participate in Burguières company business. There was a reason for that and I wasn't aware of what happened when JMB, Sr. died. It's my understanding that the older brothers must have been very wealthy at the time.

Gertrude - Where did they get their wealth?

EB - I think what happened was that Denis and Joe opened the succession and valued the estate at $300,000. Ida objected and filed suit. An inventory was ordered and the value was increased to $1 million. I inherited my grandfather's gold pocket watch. It's in the box and has his and my initials on it. He wore the watch. I did research on it and found out it's a Patek Philippe watch, terribly valuable even in those days. Turns out it's worth $20,000. He must have bought it as a young man. Then there are the canes with silver tops with initials carved in them. It's when they lived in Palm Beach in 1925 or 1926 in a time when Jules was apparently very active in civic and business matters in Florida. Leila Bristow has found a picture of the house. Jules was cunning. There were lots of letters going back and forth between Jules and Ernest, his brother, about politics, sugar supports, strategy, and tactics. That was a time when Denis P. J. and Henry were running the Company and Jules and Ernest were on the Board but out of the state. At that time I think that Jules and Ernest came back to New Orleans and became involved in the Southern States Land and Timber Company. That company bought hundreds of thousands of acres of land in Florida. Some of that became Palm Beach. By the time of the depression, much of that land was gone, but mineral rights were retained. Robert Moore, Isabella's father, lent the Company $80,000 - $100,000.

In 1936, Florence C. Burguières died. She had lived comfortably in New York. She had been interdicted and spent her entire life in a sanatorium with what sounded like schizophrenia. Patout tried to open her succession many years later and he sued the Burguières Co. and the brothers for taking her money. It looks like they did take her money to help the Company. However, they had paid for her upkeep all those years in New York. The litigation started shortly after Florence died, stopped during the war years, and then starting again after the war. Patout finally lost. The money that Robert Moore lent the Company was probably not paid back and the money owed to the Whitney Bank was treated the same way. There was a gentlemanly sense in those days that promoted the concept that you never kicked anyone when they were down. And it appears that was the case with the people that the Company owed money to. Nobody ever foreclosed. Maybe Robert got some of his money back, but certainly not interest on the money. Those were the pre-depression years. It was feast to famine in the few years starting in the late 1920's.

It must have been the prior years when they put money away. It certainly was not in the Depression. Many families lost their land but we were fortunate to save ours. It wasn't worth anything in the 1940's and 1950's but we held on. And, we had all the conflict among the siblings that made things so difficult.

OJ - Looking back, what we call our Legacy Land and what comprised the foundation of JMB was accumulated shortly after the Civil War from people who couldn't afford to pay property tax. I would guess that the land was full of timber, wouldn't you?

EB - Timber and they grew something more, sugarcane. Sugar was a late-comer to the market then. Cypress was important and hundreds of thousands of acres of cypress swamp were clear-cut in those days. The Kemper Williams family also owned a lot of land in St. Mary's Parish in those days and they clear-cut cypress. Leila Moore (my grandmother Isabella's sister) married Kemper Williams. Kemper and his brother were very active in St. Mary's Parish. However, I don't think the Burguières were in the cypress business to the extent of the Williams family.

OJ - In the early 1900's, the sugarcane business in New Orleans must have been relatively close-knit and that must have led to the general knowledge that the Burguières Co. was in trouble. Did that matter to the social position of the family in the city?

EB - I don't think so, because so many businesses were in deep trouble in those days and the operational side of JMB took place in St. Mary's Parish. My grandfather would leave on the train on Monday morning every week and come back on Thursday or Friday evening. He spent the week with his brother Jules, trying to run the Company in Franklin. There was also a small office here in New Orleans.

OJ - There's a piece of property on Prytania St. in New Orleans. The home on that property burned a year or so ago. That was the site of the Burguiéres home from 1893 to about 1919. Do you know who lived there during those years?

EB - I think Jules Sr. lived in that home and Denis P.J., Sr. lived there with some of the other siblings and children. Somewhere in the first 20 years of the twentieth century that property was sold. I don't know where the people went but what I've learned in the last few years is that of all the children, there was a city branch of the family and a country branch of the family.

Gertrude - How do you see things now for JMB?

EB - I'm really glad that the Company is still around. I'm glad that I have learned about what it accomplished, but I am not comfortable about the future. There is still a good amount of mistrust that exists and there are still people from older generations that are carrying baggage from the past. I wasn't exposed to it. It didn't make an impression on me but I'm suffering from it. There are times when I would go to a family dinner meeting and I would hear people talking about the personal problems my father had, and he did have personal problems. They mocked him, joked about him, and made fun of him. Why would a person do that? And the person making these comments had personal problems himself and had overcome them. I don't understand that. And some parts of the family are still trying to settle scores that their grandfathers were involved in 65 years ago. It's an undercurrent. And I'm sitting there not knowing anything about what they are talking about and I'm the brunt of their anger and anxiety.

OJ - Let's talk about that undercurrent. When you were on the Board the second time, the Board was relatively quiet. I know of this from talking to people. It was a time of calm. No yelling, no screaming. And yet at shareholder meetings, that undercurrent was there. What that suggests to me is that the Board members, who represented their various families, were not doing their jobs.

EB - That may be true, but let me recall a significant event that took place and started my exit from the Board the second time. That was when Philip wanted to re-organize the Board in some way, and he put a 100-page document in front of us that I hadn't seen before, and asked us to sign it. I told him I wasn't going to sign it because I hadn't read it. Richard Leefe was also on the Board and was also an attorney and is currently president of the Louisiana State Bar Association. He said he wouldn't sign it either. He said he would never sign a document that he hadn't read and didn't know what the effects would be. Well, Philip got very upset. Six months later both of us were off the Board. The reason given was that they wanted to change the size of the Board based on what was learned during the classes at Harvard.

OJ - Was the document approved?

EB - It was. The vote was four to two. We were the only dissenters.

OJ - Do you think that was the reason both of you were removed from the Board?

EB - That was a start. I've since learned that every time I spoke with Philip, I had an electrifying effect on him. I don't understand that. He's a bright, educated person and I'm a fairly bright, educated person. I don't know what it was. I don't know whether he was seeing my grandfather in me, or what.

OJ - After Richard and you left the Board, was it a functional Board?

EB - If you did what Philip wanted, it was a very functional Board. I've been on the Board of other companies and your role is one of give and take. With Philip, he didn't relish the give and take. You did what he wanted. He had thought it out and made his decision.

OJ - Where do you see the Company two generations from now?

EB - I don't know. The mitigation efforts seem to have a future, but one of the problems I see with the structure is that up until the venture into the mitigation banks, pretty much all of the post-WWII investment the Company has made, has been with partners. In other words, the Company stopped operating as a direct operating company because nobody wanted to live out in the country and run it. So we became partners with people who would run our Company for us. We partnered up with sugarcane farmers who ran our sugar business, and we got a piece. We could have made more money if we operated the sugar business ourselves, but there would have been more risk and more expense. On the oil side, we didn't drill our own wells; we leased land to oil companies. We were partnered, and thank goodness we did. We cut our risk. The same thing is true with the salt mine. Now with the mitigation banks, we are the direct players. It's high-risk high-reward. I raised a question a few years ago about local governments seeing an opportunity to make money. In my law practice and in politics I've heard about local governments and mitigation. We spend all this money now and along come these other parishes that have a lot more property than we do. They can easily undercut us in price and be in direct competition with us as they develop their own mitigation banks.

And that's happening right now. We are enjoying some good sales, but we are adding overhead. I would be more comfortable with a more cautious approach because it's a volatile field. I looked at mitigation banks in the 1990's and thought the concept was wonderful but it never got off the ground. This concept was created by the government mandating that people doing business in certain areas have to mitigate to protect wetlands. It's purely a government-mandated product and the rules could change at any time and you might be out of business. Then if local governments get involved you can see what could happen. I don't know; I could be wrong.

OJ - How do you feel about outside management and the elimination of family members on the Board?

EB - That's not a bad idea, but I think you still have to have a family Board that is engaged enough to know what the managers are doing for them. Without that the shareholders won't know what is happening in the business and can be taken advantage of. What I'm trying to pass on to those people on the Board is that they have to independently study those business units that the Company is involved in, so they can know what their managers are talking about and know if information is being presented accurately. I don't think that's happening right now. The Company is not taking advantage of some of the Board members who are great resources.